***

If you are going to start anywhere with citizen science, start here. SciStarter is the place to find, join, and contribute to science through more than 1600 formal and informal research projects, events, and tools. Their database of citizen science projects enables discovery, organization, and greater participation in science. Citizen scientists can track their conributions, bookmark things they like, and access the tools and instruments needed to get started. If you run a project, the site can help you grow and manage your volunteers.

Citizenscience.gov is an official government website designed to accelerate the use of crowdsourcing and citizen science across the U.S. government. The site provides a portal to three key assets for federal practitioners: a searchable catalog of federally supported citizen science projects, a toolkit to assist with designing and maintaining projects, and a gateway to a federal community of practice to share best practices.

One of my personal favorite projects is OpenStreetMap. OpenStreetMap (OSM) is an open data platform for mapping things that are both real and current. It includes millions of buildings, roads, trails, cafes, railway stations, parks, and more along with details about those places. You can map whatever real-world features are interesting to you! Built by a community of mappers, OSM emphasizes local knowledge drawn from a diverse community of enthusiasts, GIS professionals, and engineers who gather information using aerial imagery, GPS devices, low-tech field maps, and more. (While not strictly crowdsourcing, I can’t help but mention the project what3words, which has divided the entire world into 3m x 3m squares and assigned each a unique 3 word address.)

Zooniverse is a citizen science web portal owned and operated by the Citizen Science Alliance. It is home to some of the internet’s largest, most popular and most successful citizen science projects. The organization grew from the original Galaxy Zoo project and now hosts dozens of projects which allow volunteers to participate in crowdsourced scientific research. Projects have been drawn from disciplines including astronomy, ecology, cell biology, humanities, and climate science. It offers a feature to “build a project.”

Crowdcrafting is a web-based service that invites volunteers to contribute to scientific projects developed by citizens, professionals, or institutions that need help to solve problems, analyze data, or complete challenging tasks that can’t be done by machines alone and require human intelligence. The platform is 100% open source and 100% open-science, making scientific research accessible to everyone.

CitSci.org can support your research by providing tools and resources that allow you to customize your scientific procedure – all in one location on the Internet. CitSci.org provides tools for the entire research process including: creating new projects, managing project members, building custom data sheets, analyzing collected data, and gathering participant feedback. It can be a useful platform to gather and analyze crowdsourced data.

And just for a bit of local flavor, Washington DC has Project Sidewalk, which uses crowdsourced image analysis to identify problems with city sidewalks.

***

Dr. Sophia Liu is an Innovation Specialist at the U.S. Geological Survey Science and Decisions Center. Sophia has done all sorts of cool work. She is the Co-Chair of the Federal Community of Practice for Crowdsourcing and Citizen Ccience (CCS) and the CCS Coordinator for the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the Department of Interior. She has worked at the USGS National Earthquake Information Center, the St. Petersburg Coastal Marine Science Center, and the Energy, Minerals, and Environmental Health Programs at the National Center in Virginia.

Most recently Sophia was assigned to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to response to the 2017 hurricanes. She introduced us to a number of crowdsourced maps that were and are being used in Puerto Rico’s recovery effort. One map developed for FEMA by volunteers shows Puerto Rico’s road and hospital status in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. Another map shows locations on the island where bridges are out, power is available (or not), cell service is present, food or potable water are available, etc. In the hurricane’s immediate wake, Story Map Series provided an overview of available geospatial information from both government provided sources and crowdsourced data.

Sophia also worked on several USGS projects. One of them was Did You Feel It? (DYFI), which collects information from people who felt an earthquake and creates maps that show what people experienced and the extent of damage. Users answer easy questions about observable phenomena so that community intensity maps can be created, then integrated into other products.

She also worked on Tweet Earthquake Dispatch (TED), a project that maps people’s tweets about earthquakes. These tweets actually made detections faster than automated systems 90% of the time. They were also able to identify earthquakes that were not detected seismically.

Another project she worked on is called iCoast. Although aerial photos are often available before and after storms, researchers and responders are not always able to do much with them. Using citizen science, iCoast asks people to compare photos of coasts before and after events. The results are used for Bayesian predictions of coastal damage.

Sophia and her team at FEMA have worked with a number of volunteer network groups whose members are motivated by knowing that their efforts are leaving a positive impact. She helped FEMA recognize the value of these existing organizations and their established workflows. She and her team adapted to meet the volunteers on the platforms that they used, like Google and Slack. Sometimes hackathons are held to operationalize crowdsourcing for emergency management. Some of that material is available on GitHub.

More can be done to improve this process. To leverage crowdsourcing to better respond to hazards, Sophia recommends making hazard models more open and accessible to the tech crowds that can integrate them with other baseline data and post-storm data sets. Online visualization viewers could be improved. Independent platforms should be developed, and post-storm evaluations should be more immediate. Ultimately she thinks we can combine all of this together to create an improved playbook for emergency management.

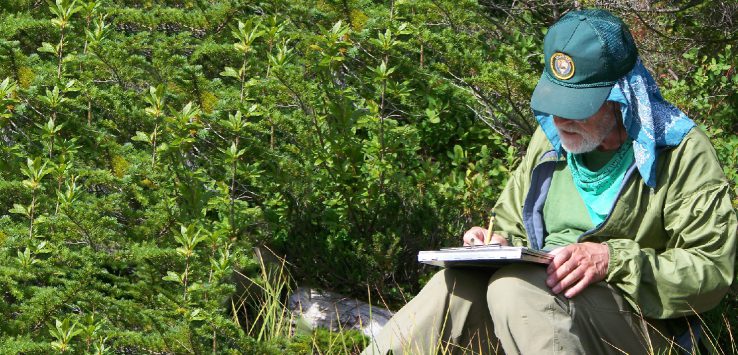

Featured image: “Citizen Science volunteer” by Mount Rainier National Park is licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image has been cropped and foliage added

Leave a Reply